For the twelfth session, we moved our focus to Chongqing. The earliest date for this sharing session was set for February 25th, then delayed to March 4th, and then pushed back to March 11th. The reason for the delay is that in the process of collecting and organizing the literature, new information is constantly being discovered, and it takes time to sort through, interview, and verify the information. It was always believed that performance art in Chongqing began in the mid-to-late 1990s, but it was eventually discovered that as early as 1985, performance art was taking place in Chongqing. This process of uncovering the truth is also quite fortuitous and dramatic; in February, at an art event at the A4 Art Museum, Zhou Bin chatted with the artist Qiu Anxiong, who mentioned that he and his classmates Zhou Jing, JiuJiu, Zhang Wei, and Liu Qiang, who had been involved in a “vandalism” activity of graffiti painting at night at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, had been working on a project in Chongqing since 1985. Qiu mentioned that in 1993 he and his classmates Zhou Jing, Jiu Jiu, Zhang Wei, Liu Qiang, etc. carried out a nighttime graffiti “vandalism” activity at the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts, and in 1994 he formally carried out a piece of performance art at his graduation solo exhibition. Although this was only one or two years ahead of the earliest known performance works in Chongqing, it was exciting enough to be a new historical discovery.

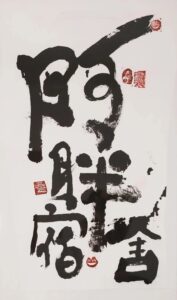

Unfortunately, it has been difficult to find photographic documentation of the event, so the archive asked Qiu Anxiong to handwrite and sign a copy of the work, as well as video interviews with those who were present at the event, such as the artist Xin Haizhou.

During that conversation, Qiu mentioned that in the late 1980s, artists such as Gu Xiong and Shen Xiaotong seemed to have done performances at university, which was really surprising information. We contacted Shen Xiaotong to check this out, and learned that in 1988, Gu Xiong created a multi-media installation/performance work called “The Net” at Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, and that Shen Xiaotong, Xin Haizhou, and others were involved in the performance portion of the work at the time. The archive conducted a video interview with Mr. Gu Xiong, who was in Canada, about the implementation of the work and the art ecology in Chongqing at the time. Later, when we talked to Mr. He Gong about Gu Xiong’s work, Mr. He mentioned that in the late 1980s, when he took over the creative writing class for the 85th oil painting graduates of the Fine Arts Department of Southwest University (then Southwest Normal University), he encouraged and promoted the creation of performance art by his students. Due to the lack of photographic material, we asked Mr. He to handwrite what happened at that time and sign the certificate. Later, artist Zeng Ni provided two images of her spontaneous behavior in front of He Gong’s installation, Forbidden Fruit of Corruption.

Up to this point, the richness of the fruits of Chongqing’s performance art history has already made us feel excited and overwhelmed with emotion. Unexpectedly, by chance, I met Tu Qiang, an artist now living in Luzhou, in Cangxin’s studio, who mentioned that he had done performance art in Chongqing in 1985, which was really unexpected. As we know, local Chinese artists first started to create performance art around 1985. So we asked the critic Cui Fuli to learn more about the situation from Tu Qiang in Luzhou, and I said to Cui, “Judge whether they were having fun at that time, or whether they were consciously creating performance art, which involves history writing, and needs to be carefully scrutinized and taken seriously. Dacui said to me after communicating with Tu Qiang: I feel that they were doing behavioral art at that time. So the work of finding graphic information and interviewing for specifics began again. Thanks to the support of Mr. Pan Zhaonan, who sent the archive a book titled “The Way of Choice,” edited by critic Wang Lin and published by Hunan Fine Arts Publishing House, in which there is graphic information documenting that Tu Qiang created a performance art work in a student dormitory in 1985, and also documenting another performance art work, “Sacrificing Myself,” which took place in Chongqing that same year, with participants such as Yin Keyu, who was a student at Sichuan Fine Arts at the time, Lan Zhenghui, Xu Zhongmin, Chen Kun, Chen Xiaoping, Yin Xiaofeng, and Lan Guozhong.

In the mid-to-late nineties, as a new generation of young people entered Chuanmei, who were influenced by the academy and the contemporary art trends in Chengdu, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and other parts of the country, performance art began to sprout and take place in Chongqing, especially in the old place of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute in Huangjiaoping, and gradually became mature and diversified. Young forces engaged in performance art activities such as Zhang Yu, Chu Yun, Li Chuan, Li Yong, Ren Qian, Pang Xuan, Huang Ru, Huang Kui, Ma Jie, Li Pinghu, Song Yongxing, Liu Boutian, Yu Xiaofeng, Liu Weiwei, Dong Xun, Liao Wenchao, Zhou Yumei, and the 8cm group have appeared and have carried out a large number of performance art activities with artists from all over the country and even from all over the world. At this point, our search for and compilation of historical documents on performance art in Chongqing has come to an end for the time being. We hope that more people will provide us with information and continue to fill in the gaps, so that we can eventually restore the original history as much as possible.

Art critic Lu Mingjun writes in his article “Lanzhou Modern Art in the 1980s” that “oral history” itself carries a certain degree of criticality in it, and every witness always inevitably mixes more or less critical consciousness in the process of reminiscing. Of course, the writing of history is often the result of the subject’s criticism. Especially when it comes to the subject’s interests and personal privacy, the narrator consciously avoids talking about it or gives another explanation. I think that this is exactly where the limitations of “oral history” lie, “the word of mouth”, after all, only from the mouth of an individual fact is still doubtful, at least not completely sure, not to mention, we often encountered precisely for the same thing, the parties concerned What is more, we often encounter precisely the same thing, the parties involved in the mouth and different facts and attitudes. This means that “oral history” will always be uncertain until the day when we actually find historical sources to support it, and then we can construct a framework of possibilities. …… Under the premise of such a scarcity of documentation, all we can do is to present the interviews of more than twenty people in front of the world, even if many of them are contradictory and conflicting, but it’s not Zhou Bin‘s intention to be right or wrong, or to leave them to be confirmed by history.

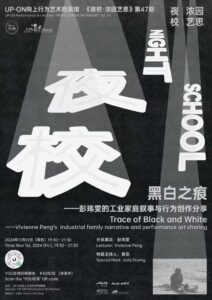

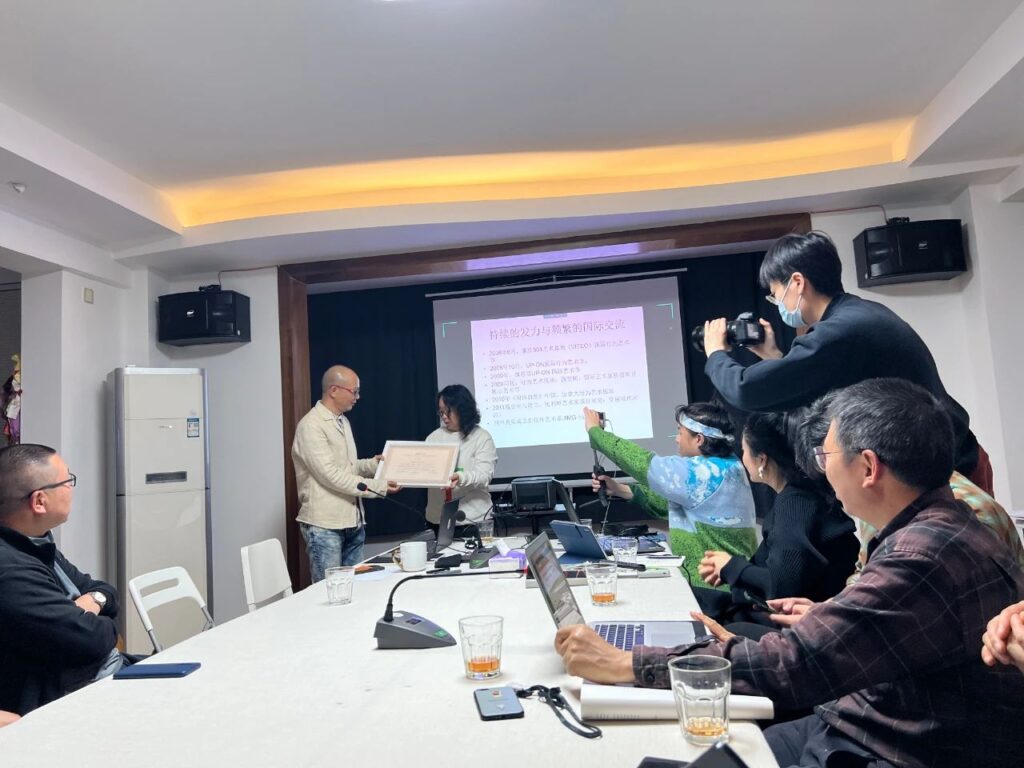

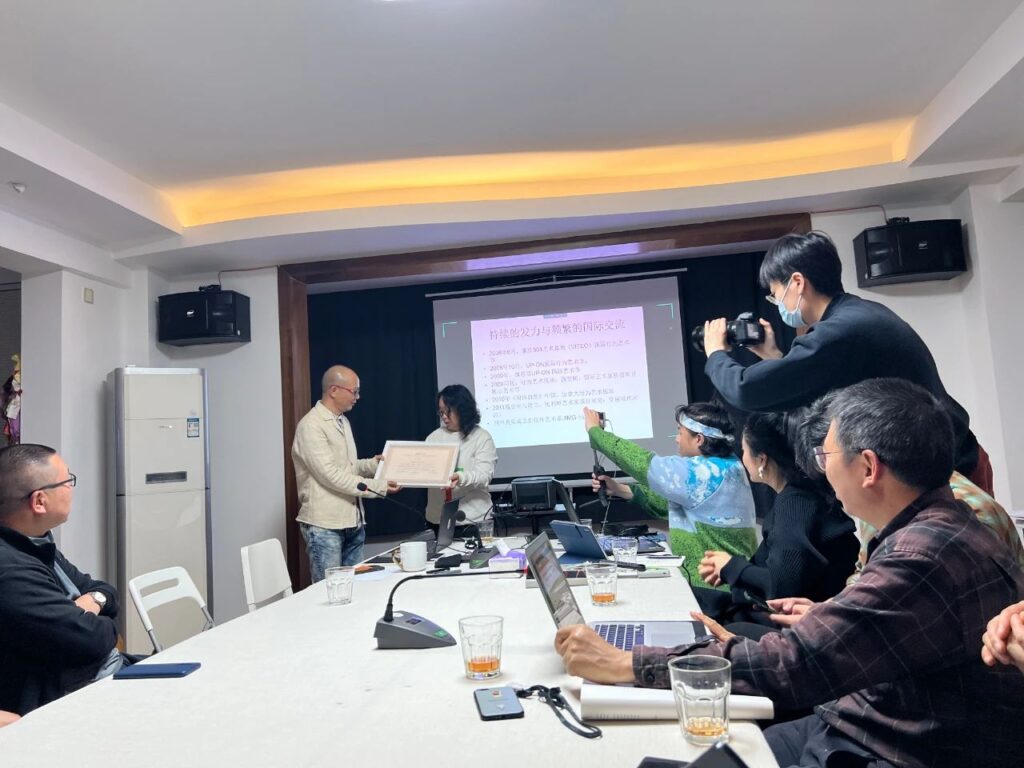

2023, March 11th, 19:30 pm, the twelfth session of “Looking back to the Past”, “Archives of Chongqing Performance Art 1985-2010”, will be held in Chongqing. 1985-2010” will be held at the Archives. The reason for stopping at 2010 is that performance art in Chongqing has changed a lot since then, both in terms of the organization of its activities and the way it is created, and a large number of performance art activities and works have appeared, which will be sorted out in a separate unit in the future. The Archive is honored to have invited artist Ren Qian to host this sharing session. A video interview with the artist will be shown, and some precious documents will be displayed, which will help us to have a more vivid and in-depth understanding of the artist, his works, and the ecology of performance art in Chongqing. The work of collecting and organizing historical documents is complicated and requires the cooperation of colleagues. The archive is sincerely grateful for the support of many colleagues, such as He Gong, Gu Xiong, Qiu Shixiong, Tu Qiang, Wang Lin, Shen Xiaotong, Xin Haizhou, Cui Fu Li, Ni Kun, Li Yong, Tian Meng, Pan Zhaonan, Yan Yan, Zeng Ni, and so many others, which are too numerous to mention in detail. Of course, special thanks to the artist Renqian, who with great enthusiasm and patience, has put a lot of effort into collecting and organizing the materials. It is gratifying to believe that the significance and value of these efforts are enough to reward our dedication.

The Archive is honored to have invited artist Ren Qian to host this sharing session. As one of the most important artists in the field of performance art in Chongqing, he tells the story of performance art in Chongqing with the clue of time: in 1985, when artists in mainland China first started to create performance art, the creation of performance art in Chongqing had already begun at the same time. Since then, although it has only occurred sporadically, it has been passed on from one generation to the next and flourished in the 1990s. Although it experienced a decline at the beginning of the 21st century, around 2007, it started a prairie fire, which has continued to this day. This time, the archive of Chongqing performance art was compiled up to 2010, because performance art in Chongqing has changed and developed greatly since then, both in the organization of activities and in the type of creative language, and a large number of performance art activities and works have appeared; this part of the documentation will continue to be collected and compiled, and will be shared in a separate unit in the future.

The sharing session featured video interviews with artists who participated in the early days of performance art in Chongqing, such as artists Gu Xiong, He Gong, and Tu Qiang, as well as participating creators Xin Haizhou and Shen Xiaotong. One key word appears frequently: breaking through the wall. Those long-ago stories, rich in youthful hormones, full of longing, spontaneity, courage and uninhibitedness, move the listener, while the passage of time and the passing of time also make people feel sad and emotional. Rarely, some artists who had created performance art works in Chongqing, such as Liu Chengying, Zhang Hua and He Liping, also came to the scene and shared with us their concepts and feelings of creating those works at that time. There were also some precious documents on display, such as old newspapers that reported on performance art in 2002, artists’ manuscripts, books, posters, invitations, etc. These various forms of precious materials can help us to have a more vivid and in-depth understanding of the artists’ creative thinking, their creative situation, and the historical development of Chongqing’s performance art ecology.

During the exchange session, audience members with diverse identities asked questions and expressed their feelings from different perspectives, while critics such as Cha Changping, Tian Meng, Ding Fenqi, Li Huiwu, and Zeng Qunkai talked about the ecology of performance art and the state of artists’ creativity from professional perspectives. Tian Meng and Ding Fenqi, both of whom have studied and lived in Chongqing for many years, not only talked about their own observations and feelings, but also added important insights into small-scale, unrecorded performance activities.

Cha Changping: It is difficult to reconstruct the behavioral scene from today’s perspective. This reflects a fundamental problem: when we face the real historical events. In fact, we can only get infinitely close to this world, but cannot restore it in all aspects. As a participant and a bystander, the perspectives and attitudes of things are different. Participants have a very important phenomenon within historical narratives, that is, they emphasize the importance of their own works. Therefore, we need to pay more attention to objectivity in speaking and writing about historical events. Serious writing with multiple perspectives and mutual corroboration. Oral tradition has always been at a distance from real historical events. The academic value of the archives is reflected in this difficult exploration of historical truth.

Critic Li Huiwu made a suggestion from the perspective of art history revision: archives are a general knowledge that may require the writer to make an overview of self-attitude from the preface. The accuracy of the information is extremely important, but the personal attitude of different writers. “how I see it,” is also extremely valuable.

Zeng Qunkai: Tracing the threads of history, there are many differences in the way history is organized in different regions and time periods, but there are still commonalities under this appearance. There are also differences between art history and contemporary art history. Traditional art history has clearer and more traceable clues, while modern art history has a specific situation after the reform and opening up of the mainland, which is not necessarily applicable to a specific traditional lineage. In terms of art materials and materials, it does not have the so-called contextual relationship; it is more of a geographical and spatial speech, or an awakening. Such a gesture is very different from the traditional research method of art. On the other hand, it is more spontaneous and autonomous, and we can only use the relevant literature as a basic source of material to explore an effective research method. In addition, for literature, the work done by different professions determines the way of combing, for example, artists will pay more attention to practice in the process of combing compared with researchers. The atmosphere was lively, and the seminar ended overtime, as usual.

During the sharing session, the artist Ren Qian donated to the archive some precious documentary materials (event posters, books, manuscripts, pictures, images, etc.) that he had kept for many years for his performance art. These materials will be categorized and filed, properly stored, and become public assets for readers and researchers. The collection and organization of historical documents is a complex and complicated task that requires the cooperation of everyone. Here again, the Archives would like to sincerely thank the many colleagues for their support, such as He Gong, Gu Xiong, Qiu Xianxiong, Tu Qiang, Shen Xiaotong, Xin Haizhou, Cang Xin, Cui Fu Li, Ni Kun, Li Yong, Tian Meng, Pan Zhaonan, Yan Yan, Zeng Ni, and so on, sorry for the difficulty in detail. It is also with the selfless support and help of these colleagues that the Archives can develop healthily and do better and better.

This issue of Warm Up combs through the history of performance art in Chongqing before 2010, and we have begun to collect and sort through the documentary archives since then. It is clear that there have been significant changes after 2011 compared to before, both in terms of the number of events and works, as well as the diversity and specialization of artistic language forms. In particular, from 2012 to 2017, performance art entered the Department of New Media Art at Chuan Mei as an official course, an unprecedented move that not only greatly promoted and optimized the ecology of performance art in Chongqing, but also had an impact on the wider region of the country.12 years and what has happened in the meantime? Let’s look forward to the sharing session of “Warming Up” Chongqing Performance Art 2011-2023.