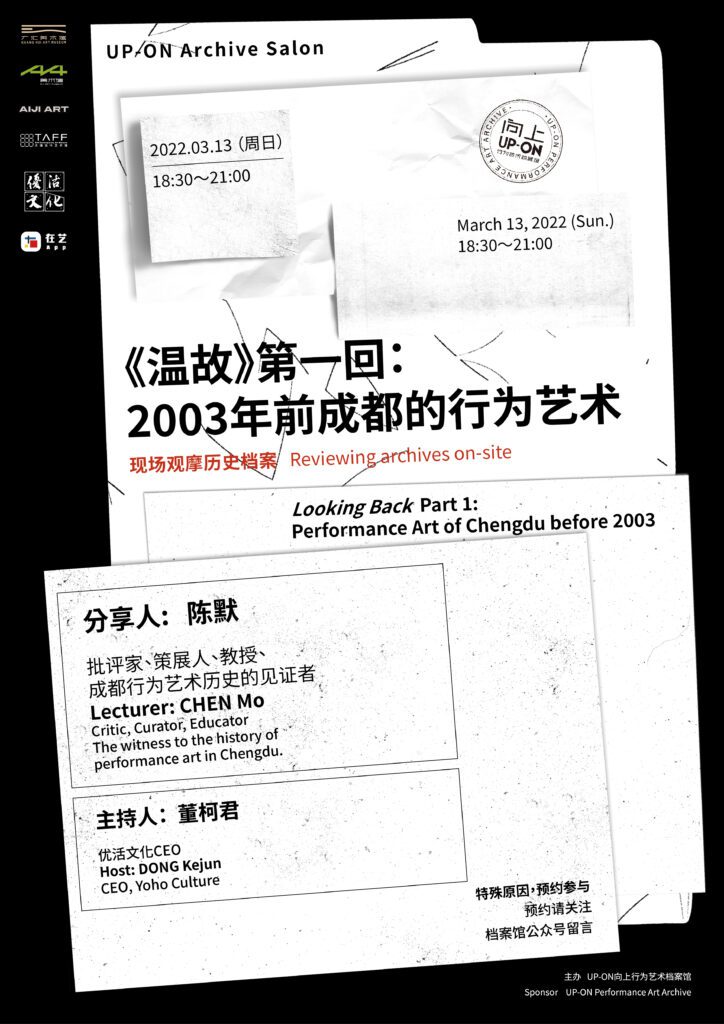

Postscript to the first installment of “Looking back”

On March 13th, 2022, at 7:00pm, the first edition of Warming Up: “Performance Art in Chengdu before 2003” started on time at the Archives. After introducing the original intention and work plan of the Archives, Zhou Bin paid tribute to Mr. Chen Mo, who had donated a large amount of performance art literature for free, and presented him with a certificate of collection.

Five critics, curators, artists and organization founders who have long been close to performance art were invited to sit in the archive and share their stories with us. In the first half of the session, Mr. Chen Mo answered various questions raised by the audience in the course of the document review. There was a strong sentiment that the media environment before 2003 was so open! Pictures of bare-assed performance art could appear on the front page of the newspaper along with the speeches of provincial party secretaries. And which will be better, the present or the future?

The second half of the sharing session moved to the rooftop of the Archives. Mr. Chen Mo projected a large number of documents and gave a brief explanation. He tried to give everyone a macro-perception of the atmosphere of Chengdu performance art in that era.

In the interactive session, Liu Chengying, Yu Ji and Zhou Bin, the first generation of Chengdu performance artists, a former member of the Chengdu underground music scene, responded to some of the questions raised by the guests.

Summary of questions:

Zhang Sanfeng (media person and writer): What is the reason for the sharing session to introduce Chengdu’s performance art with 2003 as the time point?

Chen Mo: Before 2003, documenting literature was more about film and analog video, and then digital. The change in the way of documenting is one of the reasons.

Zhou Bin: I would like to add that around 2003 can be regarded as an important watershed in the development of performance art in China; in 2001, from CCTV to the symposium of the Association of Fine Arts, and from the temple to the marketplace, there was a big discussion about performance art, and the overall conclusion was that performance art was bad art, or even not art. The Ministry of Culture issued the “Notice of the Ministry of Culture on Resolutely Stopping the Performing and Displaying of Bloody, Brutal or Obscene Scenes in the Name of ‘Art’”. Performance art was completely demonized and became a street rat. This gave great psychological pressure to artists engaged in the creation of performance art, and around 2003, China’s art market heated up rapidly, and performance art, an immaterial art medium that is difficult to enter the market, was further marginalized. Based on these two points, we take 2003 as a time point to introduce performance art in Chengdu.

Zhang Yuan (anthropologist): The concept of behavioral art starts from an anthropological point of view; it is a body-mediated expression of the desire for freedom and excitement, and it also shows a strong social concern. Behind the social concern shown by performance art is the political issue. So, I am puzzled by the fact that expression has become difficult and extravagant at the moment, in other words, when political expression is not smooth, when rigid and hard laws and institutional designs are against the “inherent moral spirit of the society”, how can performance art bring about the possibility of being an alternative voice?

Zhou Bin: I think insisting on individualism and emphasizing individual expression is the starting point of all possibilities.

Arjun (bookstore manager): What is the bottom line of performance art creation?

Zhou Bin: Personally, I think one is not to harm the lives of others or animals. The second is the law, but the law has a gray area, so it is flexible.

Yu Ji: I don’t think there is a bottom line.

Li Yuankai (Graduate Student, Curatorial Program, Chuan Yin Academy of Fine Arts) : Some time ago, a performance artist scattered golden rice grains in the Huangpu River to satirize people’s waste of food, which is a meaningful piece of work in my opinion. But to the general public, it may seem like claptrap? I would like to ask: Is a piece of performance art still meaningful on the premise that the public may not understand it and it has not been recognized? What can the artist gain from it? Can the experts here answer this question? Thank you! Thank you!

Yu Ji: First of all, works of art do not always have to have a practical meaning; often, they are created by the artists themselves as a result of their own feelings, and this is especially true for performance art. Again, I think the public’s lack of understanding of performance art may be due to their lack of understanding of this form of art, which is why there is a need to enhance the public’s knowledge. For example, if the public can understand a piece of Chinese painting, no one will question the significance of this work, because Chinese painting has a history of thousands of years, and under the cultivation of this history, everyone can appreciate Chinese painting, but of course, the public may look at the surface, and it is unlikely that they can appreciate the work from a professional point of view.

Chen Mo: Right, if you want to ask questions about behavioral art, you must first have a basic understanding and knowledge of the history of this art. Behavioral art has a long history in the West, with more than half a century of development.However, as China has only a very short history, there is still a lot of groundwork to be done.

Yu Ji: As for the gain and significance of the artist himself, I don’t think this question can be answered, you can only ask what kind of significance a certain piece of work has for the artist. There are so many works, and each of them has his or her own thoughts at that time, even if the public thinks it is meaningless, for the artist himself or herself, it is a kind of self-fulfillment, which is also meaningful.

In addition to the first generation of Chengdu performance artists, there were also He Liping and Ye Cai Bao from the second generation, and Li Aishao and Li Yao Yao from the fourth generation. They all talked about their feelings.

He Liping: The most important thing that I have gained through performance art over the years is how to think about my works in the context of contemporary art, and the other thing is that performance art makes me keep thinking.

Ye Cai Bao: In fact, I studied printmaking in Xinjiang in college, and at that time, I also came into contact with performance art, but I only learned about it through the Internet and reading books, and then I learned that Chengdu’s ecology and atmosphere for performance art is very active, and that’s why I came to Chengdu. I believe that performance art uses the body as a medium, it can be a political expression, a social expression, or an expression of one’s own emotions, it expands the expression of our bodies, and it is very worthwhile for us to explore.

Li Yao Yao: I came into contact with performance art at the end of my 21st year, and I was deeply touched and gained a lot. When I use my body as a tool to express myself sincerely, it brings me great satisfaction. For me, performance art is a space constructed by the artist himself to express himself sincerely and enjoy himself fully.

The sharing session was delayed until nearly ten o’clock, and the group of people who were not yet satisfied continued to enter a state of loose talk. The rooftop was warm and the beer donated by Mr. Chen Mo was quite popular.

Photos from the sharing session